The ’80s were a different time. That’s all I have to say about that. Oh, except that I cheated with the title to make it snappier–some of these are rated G.

5. The Last Unicorn

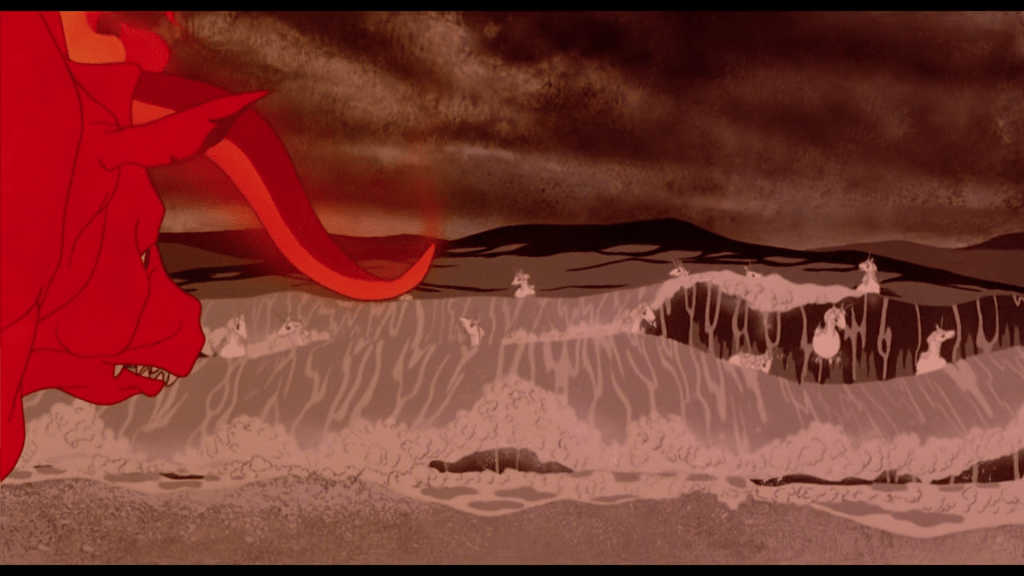

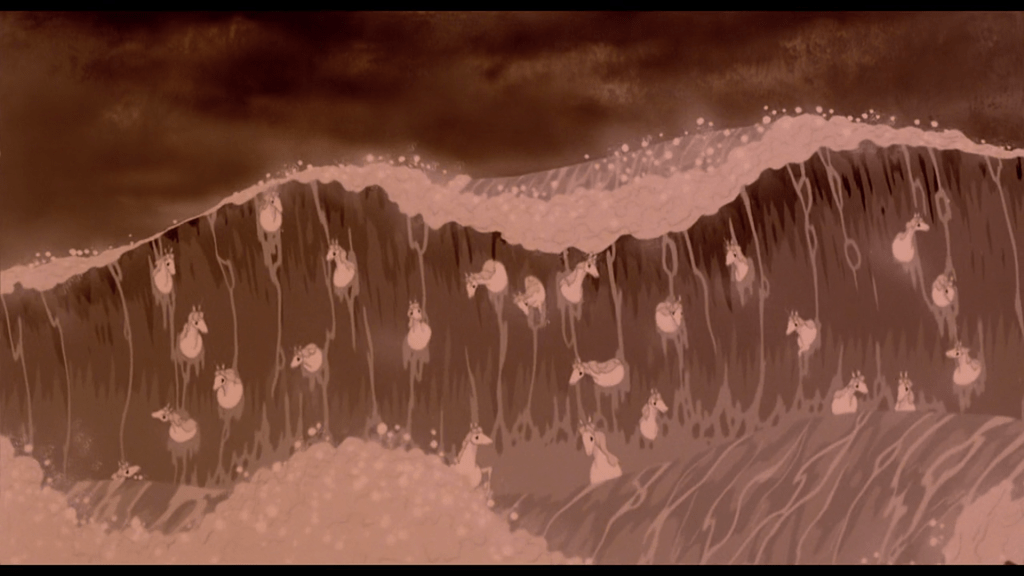

A Rankin/Bass production, but not nearly so touchy-feely as their Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer movie. A unicorn wonders why she hasn’t seen any of her pals lately, and it turns out that cruel King Haggard has a giant bull that chases them into the sea so he can watch them, because it’s the only thing that makes him happy. (Yes, this movie’s just as cheerful and life-affirming as it sounds.) In order to hide from the bull, her magician friend Schmendrick turns her human, but as she’s used to being immortal, her decaying corpse of a body freaks her out. Despite falling in love with Haggard’s son Lir, she’s no Disney princess. In fact she spends much of the movie being an arrogant twat. I still enjoy it as an adult, but I’m not sure what appealed to me about this movie as a child, unless it was the creepiness factor.

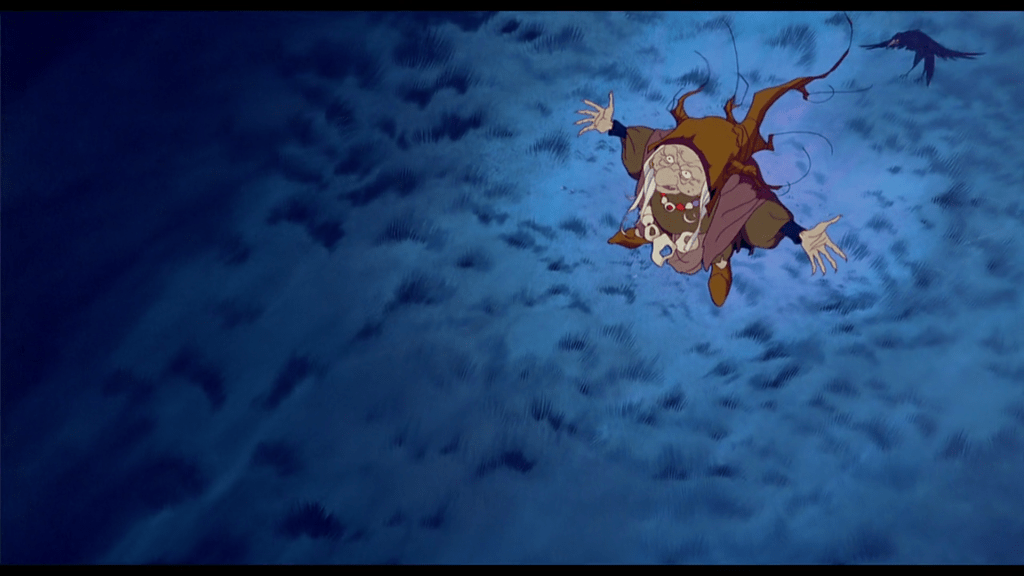

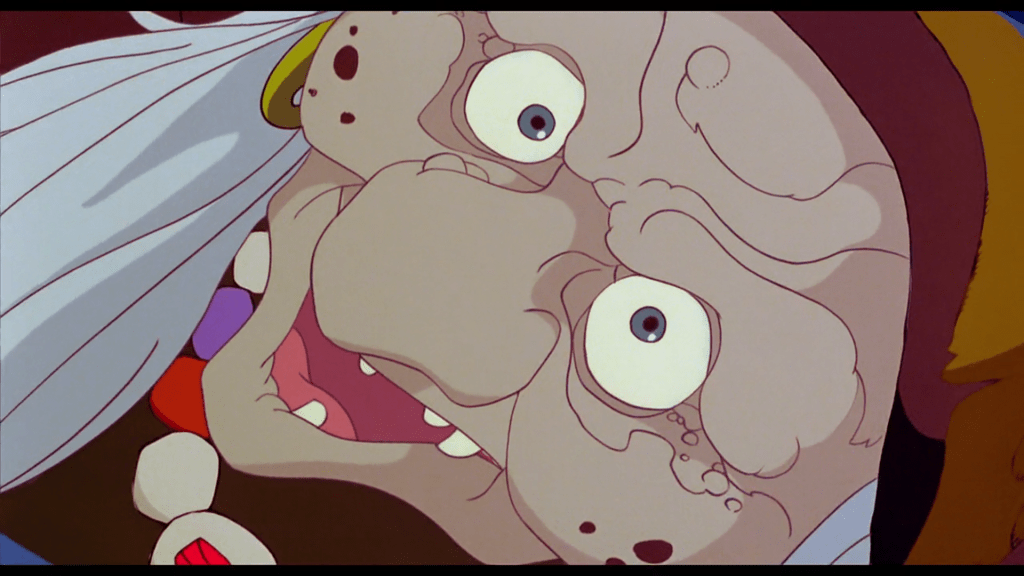

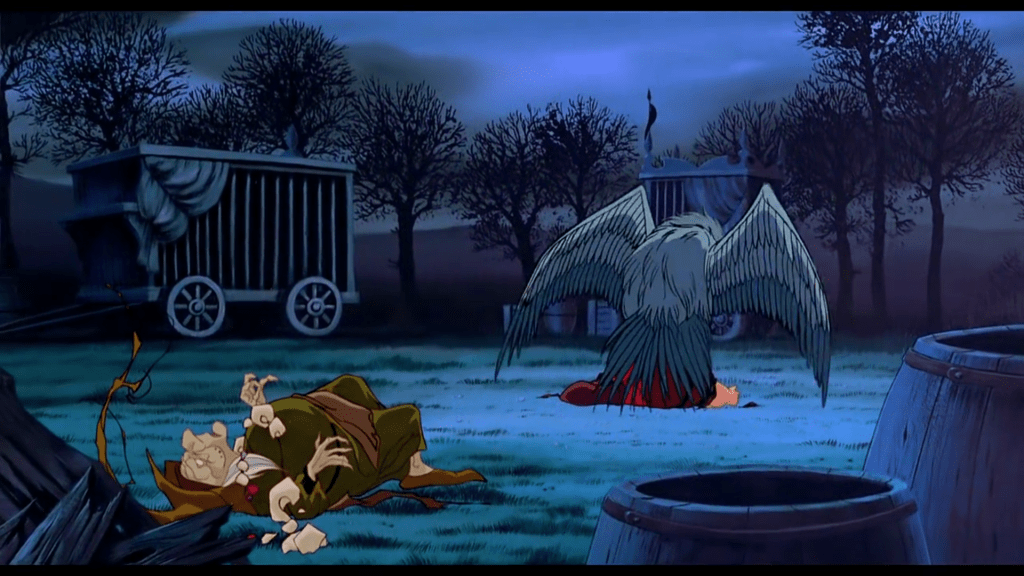

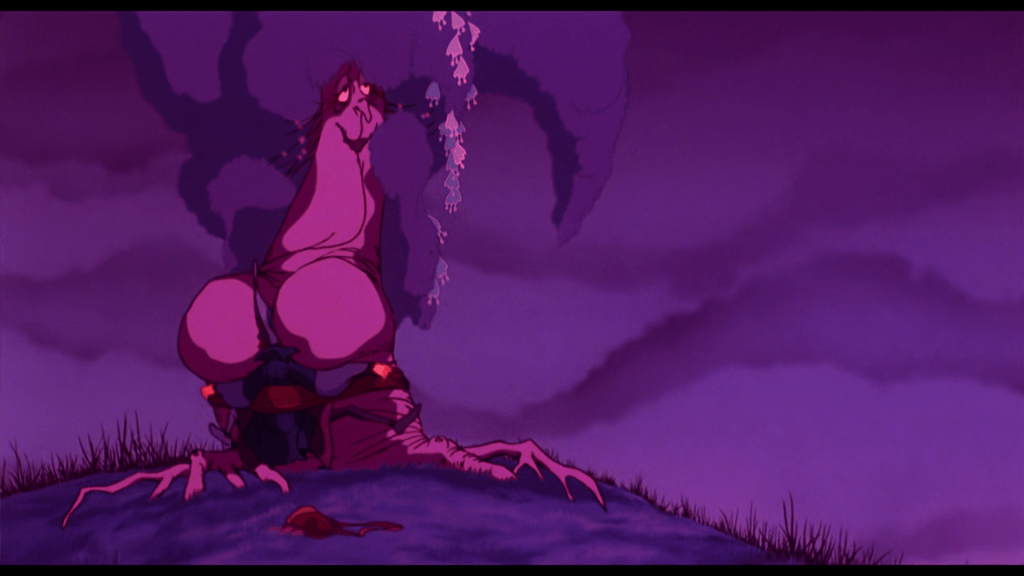

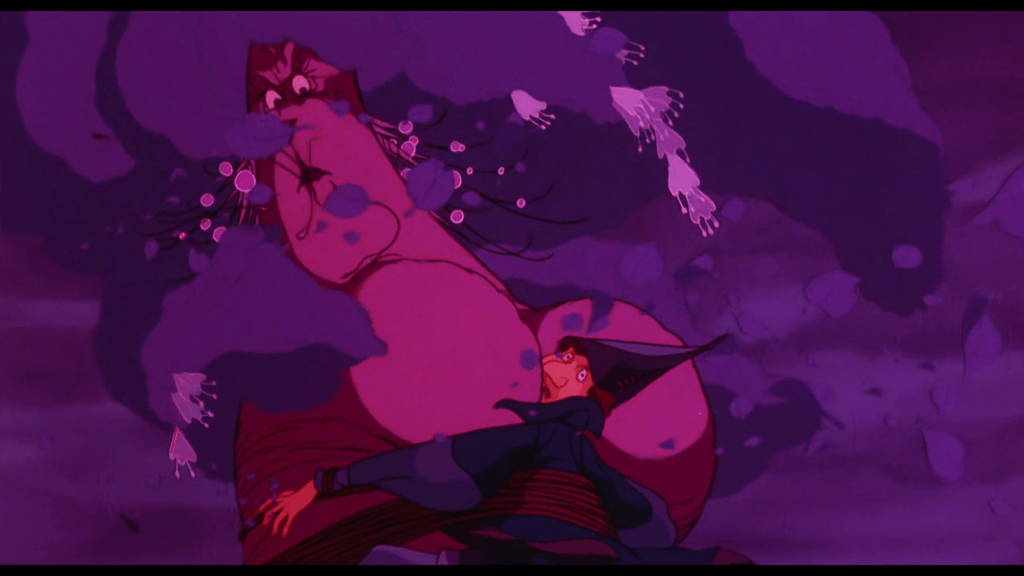

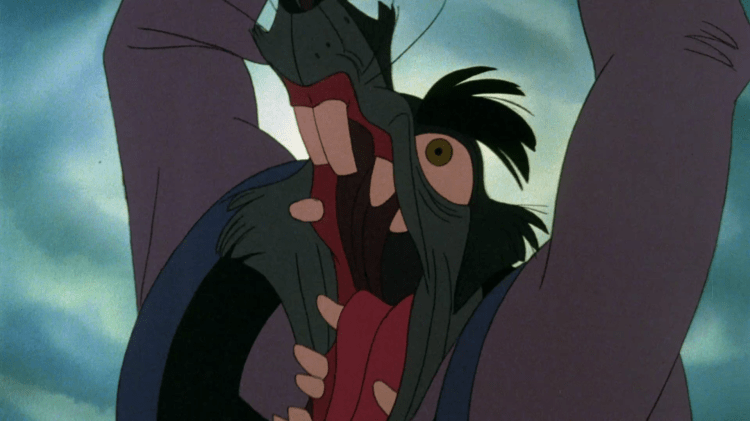

Consider the following sequence: the unicorn has been taken prisoner by carnival owner Mommy Fortuna. She’s also in possession of a harpy, which is REALLY pissed about being in a cage. Does Mommy Fortuna care? Nah. She’s like, “Welp, she’ll kill me one day. Whatevs. Yolo.” The unicorn frees the harpy, which by the way has three boobs just a-hangin out, nipples and all, and may I remind you this movie is rated G, and she indeed kills Mommy. You can see her corpse in the foreground as the harpy also goes to town on Mommy’s fuckwit assistant.

Also disconcerting is the scene when Schmendrick is tied to a tree that becomes sentient and acts distinctly sexually harass-y. She virtually smothers him with her big tree bosom.

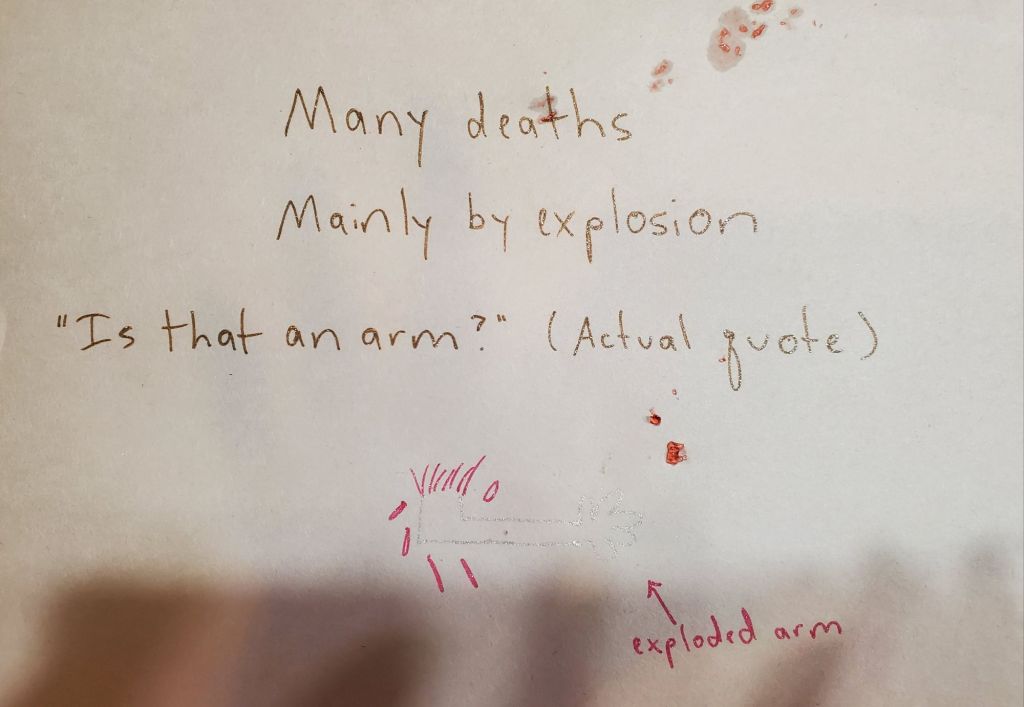

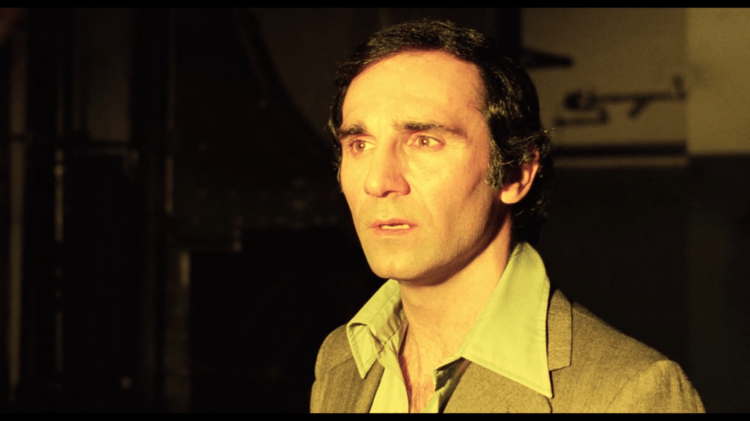

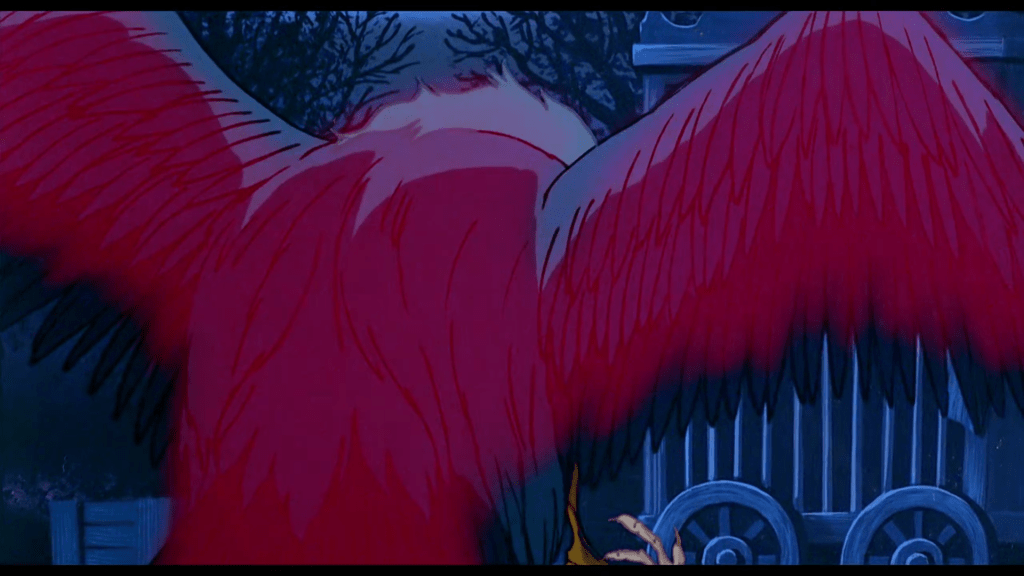

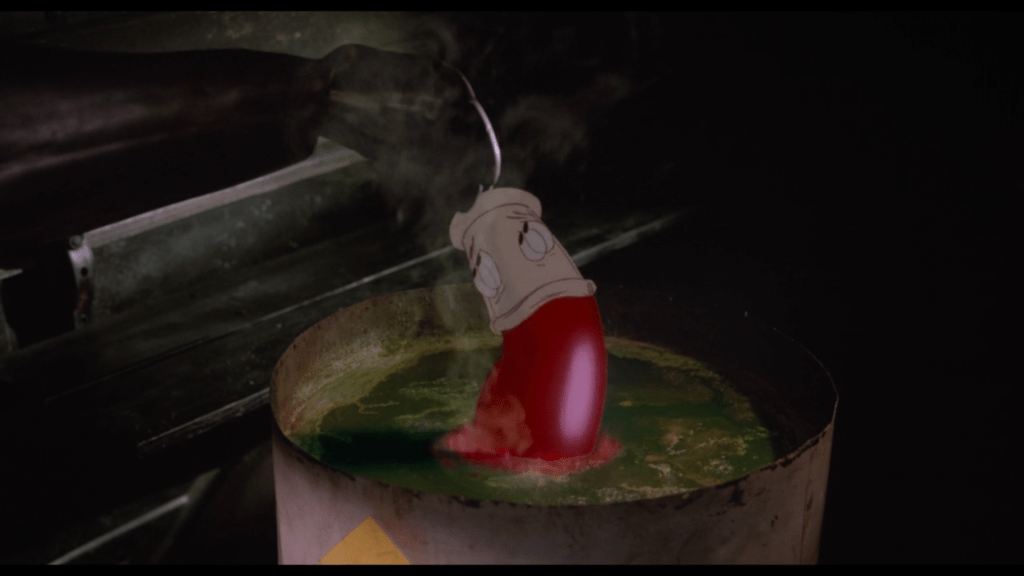

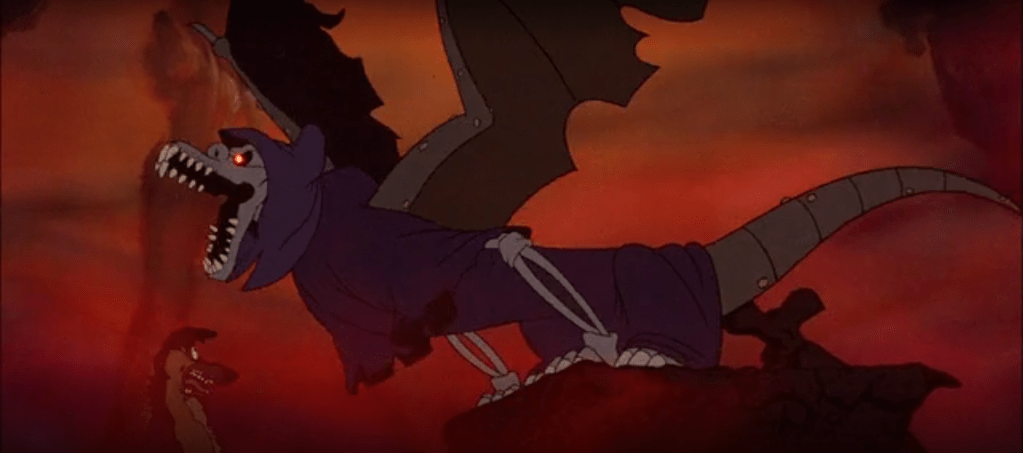

Here’s the red bull chasing the unicorns into the sea. Wholesome family watching all around!

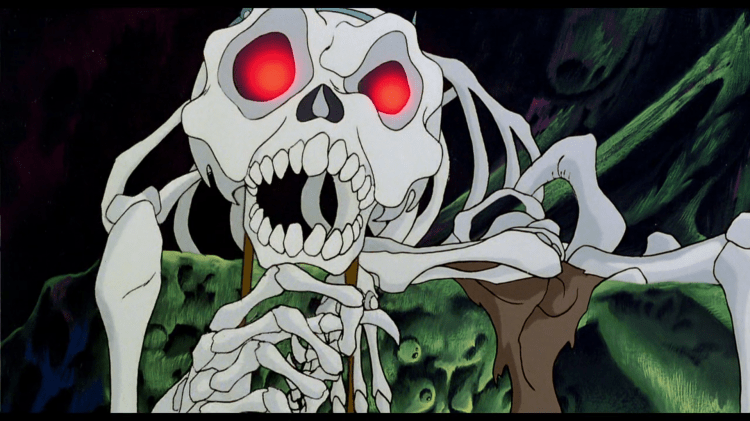

4. The Secret of NIMH

This is a movie by Don Bluth, the man who left Disney to make his very own child-traumatizing tearjerkers about dead parents. The very first line of the movie is “Jonathan Brisby was killed today while helping with the plan.” The plot centers around Jonathan’s widow Mrs. Brisby, a field mouse who has a deathly ill son and needs to move her house before the farmer who lives adjacent plows his land and crushes her family to death. As a mouse, she faces all number of dangers, including a plow, a malicious cat, a giant owl, and hostile rats. The rats are supersmart because they were experimented on in a lab. During a flashback we’re treated to images of hyperventilating bunnies, a fearful mother monkey and her babies, whining puppies, and rats getting shots in the gut with bigass needles. The only comic relief in the movie is Jeremy the crow. And occasionally the children. Except at the end of the movie, when they’re drowning in mud. We’re talking about a character getting crushed by a cinder block, leaving some of his limbs sticking out.

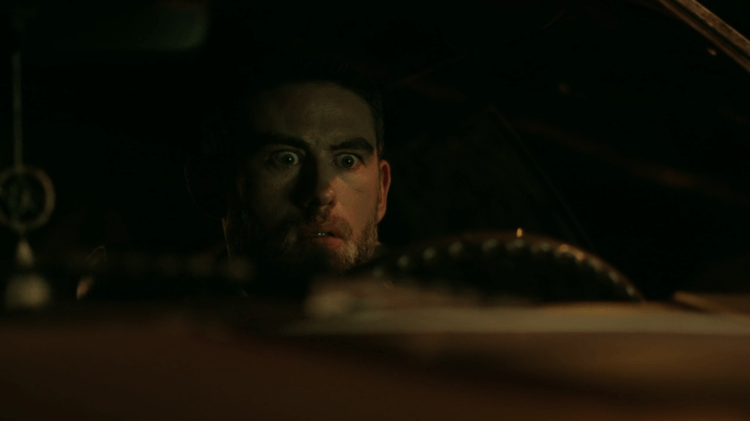

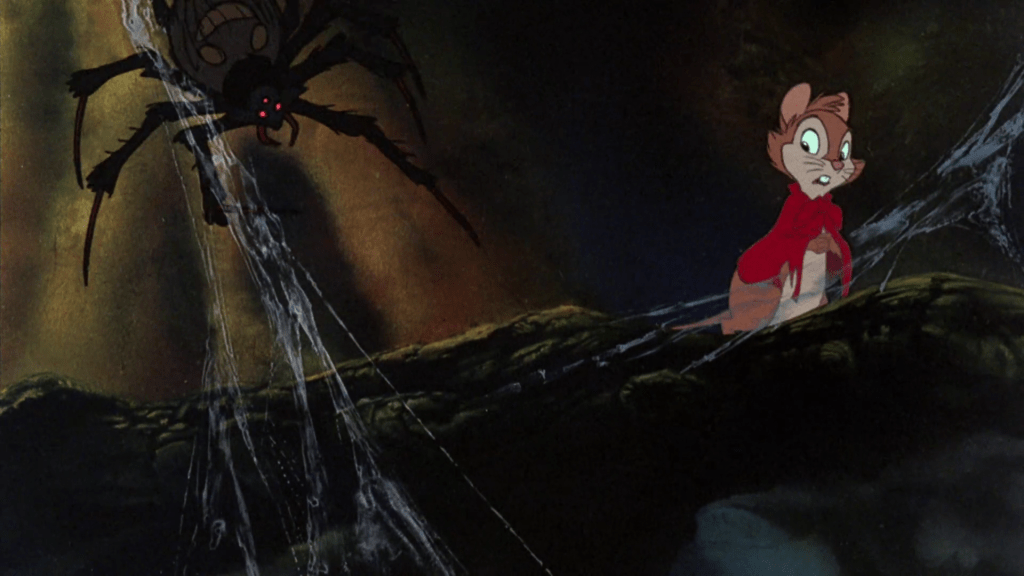

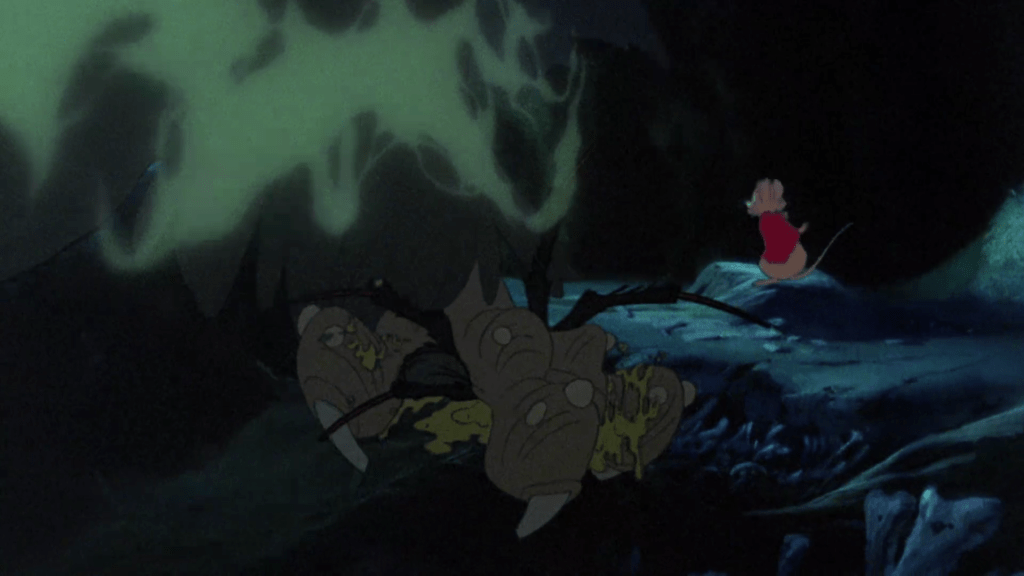

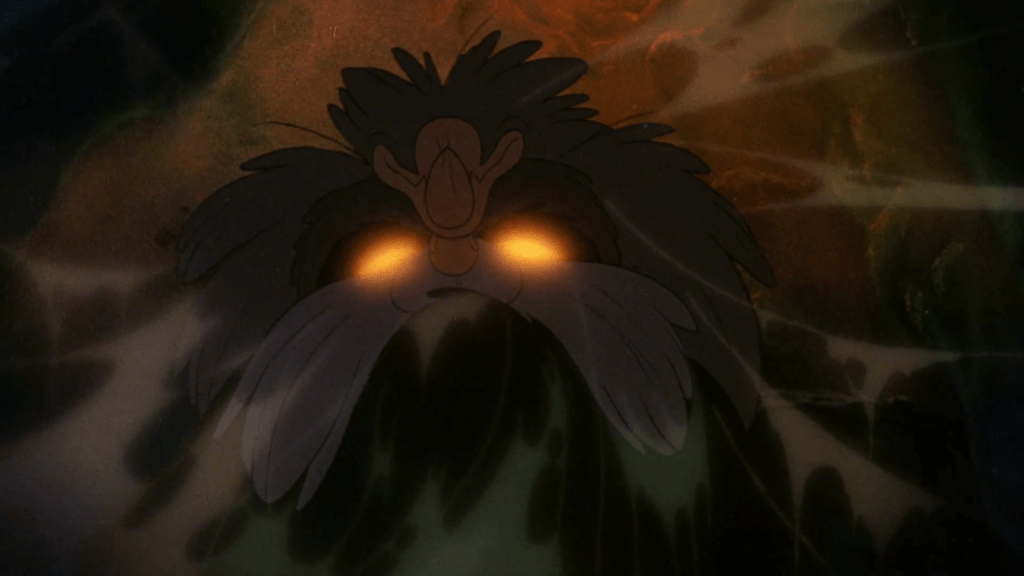

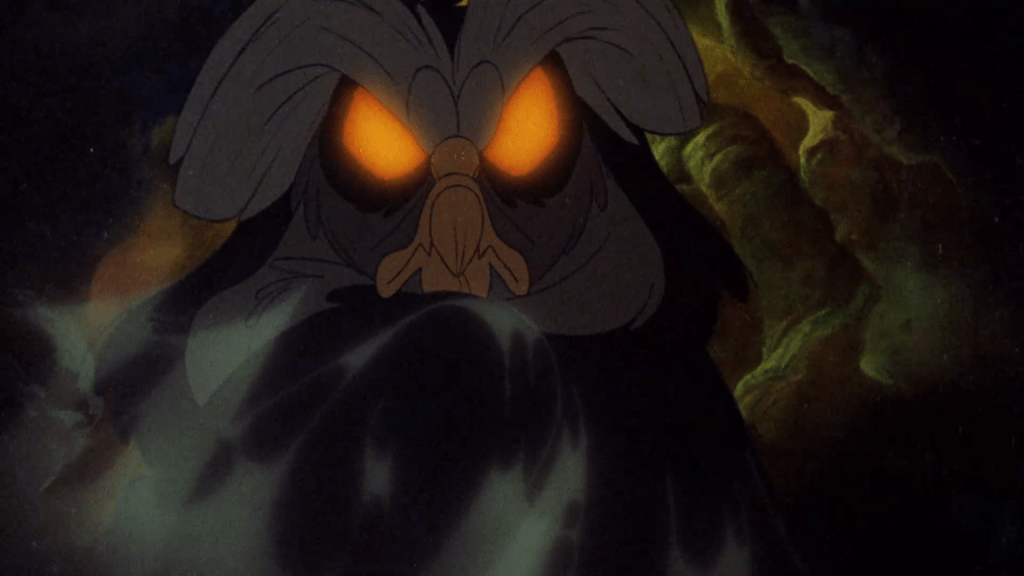

Lookie here: Mrs. Brisby ventures off to see the Great Owl, not generally a friend of rodents. She is followed by a gigantic, terrifying spider, drooling with the anticipation of eating her. The Great Owl crushes it to goo, shocking Mrs. Brisby. We then see that his head is upside down, and he flips it around. For good measure, his eyes are glowing and he’s completely covered in spiderwebs.

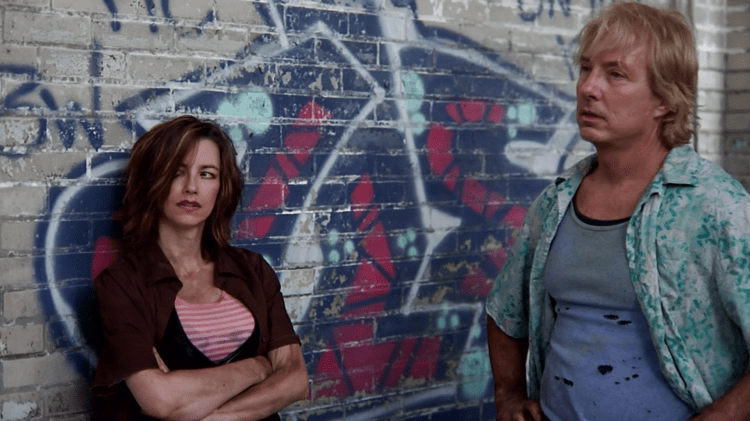

3. Who Framed Roger Rabbit

Hollywood, 1947. Eddie is a tough gumshoe who’s mixed up in a murder case involving live folks and animated characters, who exist in the world of humans but live in segregation from them. The special effects are amazing, especially for the era.

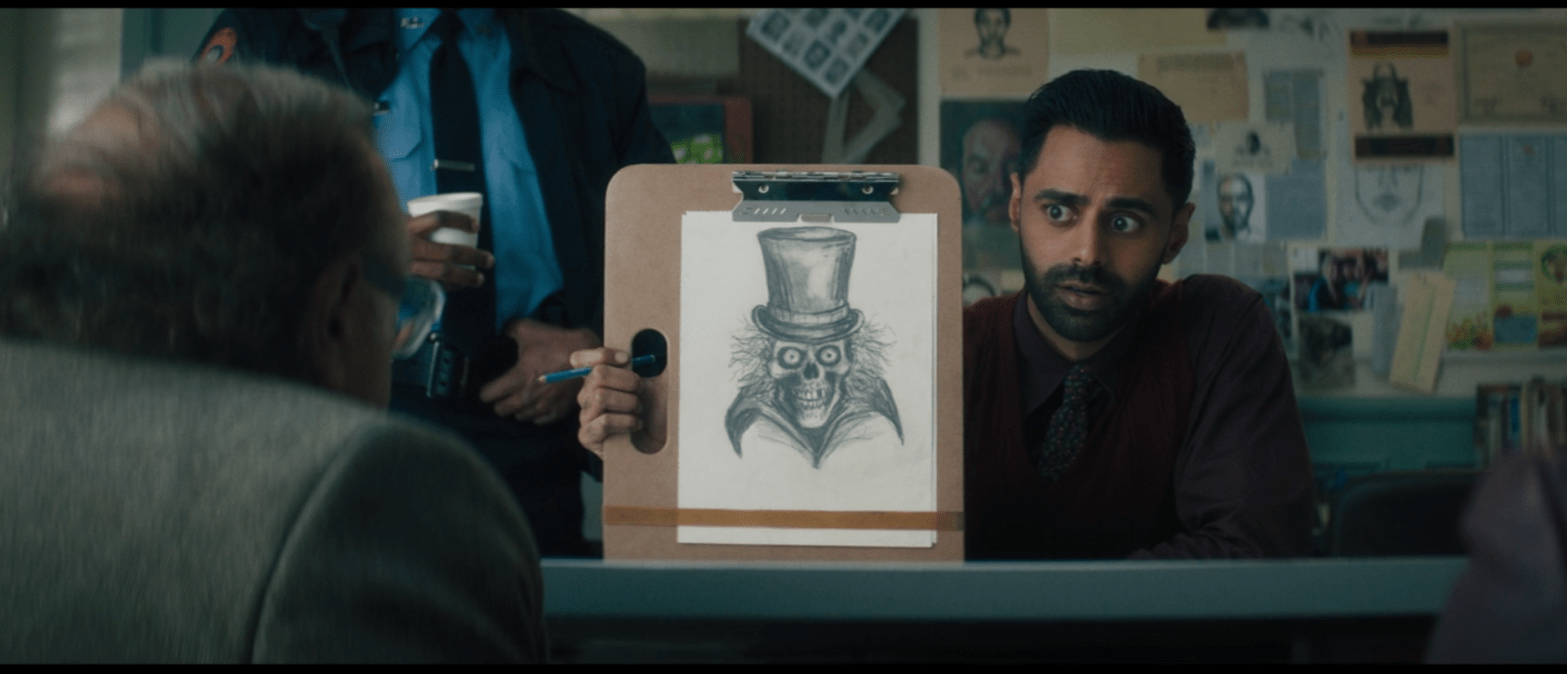

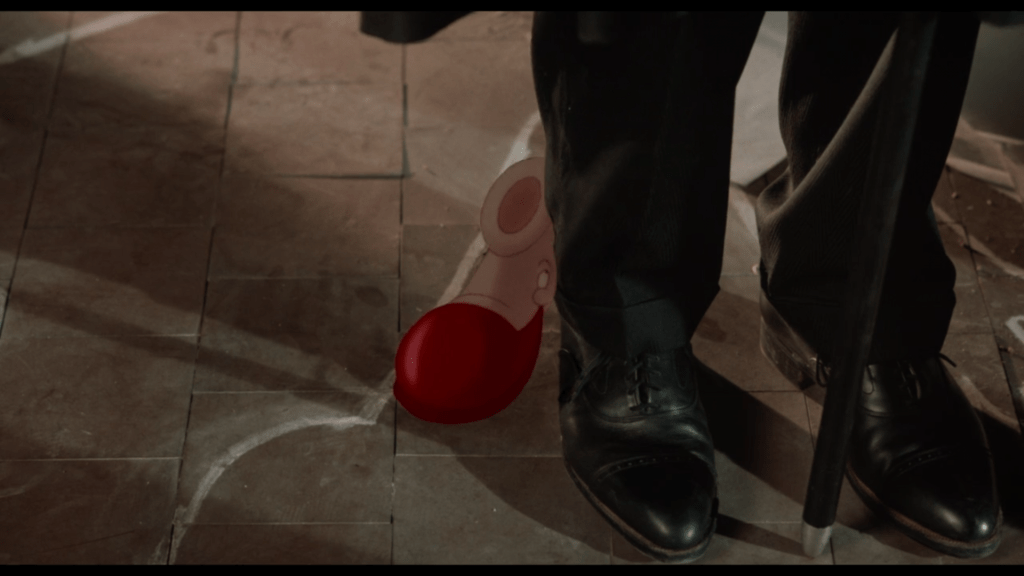

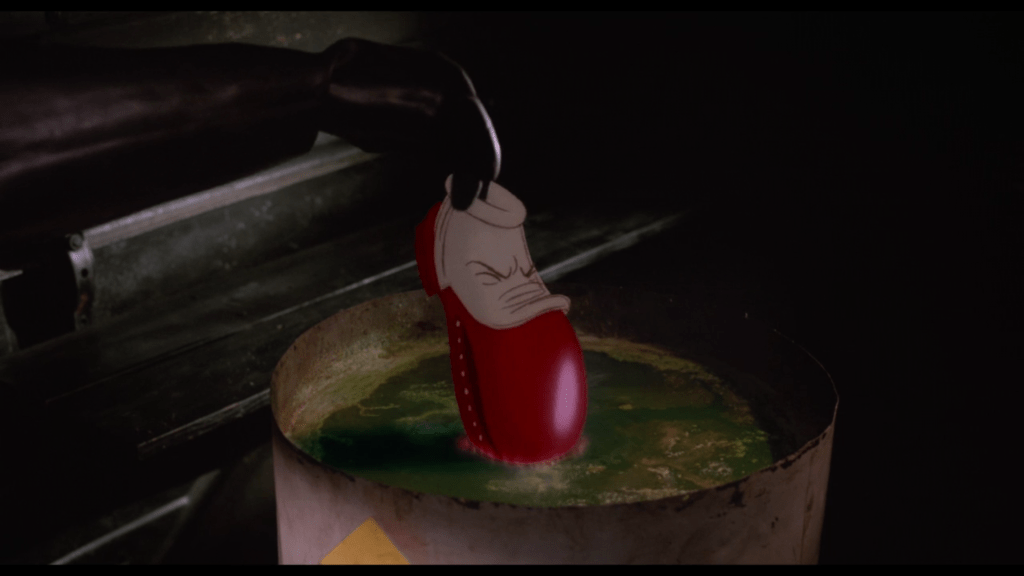

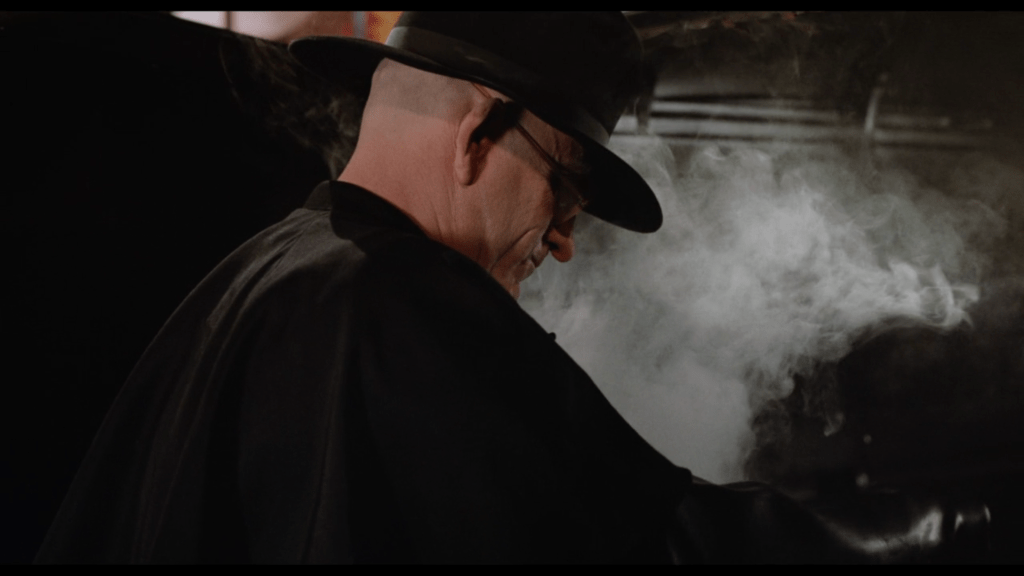

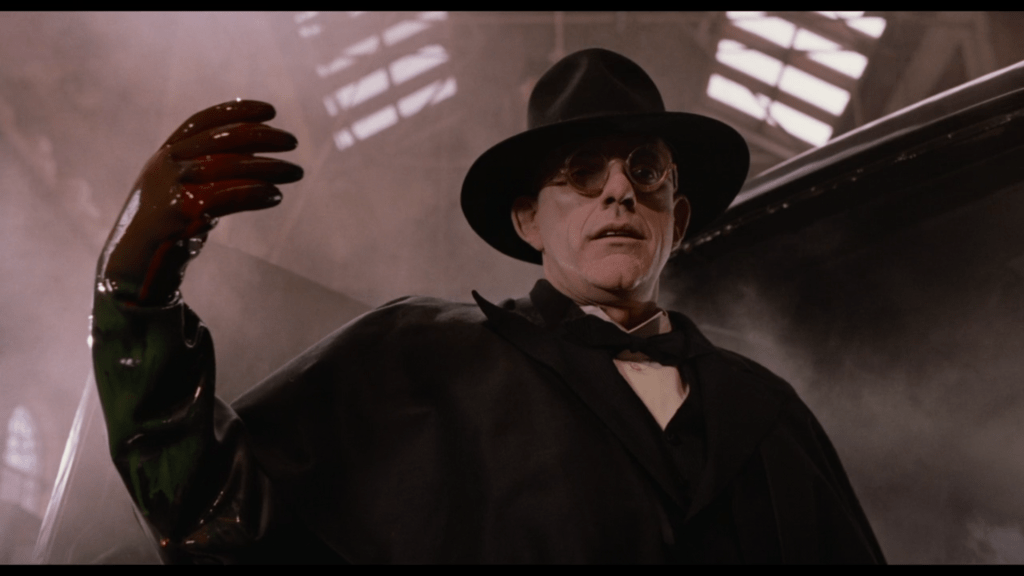

Eddie’s nemesis is the evil Judge Doom, who really hates the cartoons. Here we have a scene when a childlike shoe nuzzles his leg. Doom, illustrating that he has a new way to kill toons, picks up the shoe and melts him alive while the little feller gazes at him beseechingly. Doom emotionlessly displays his dripping red glove.

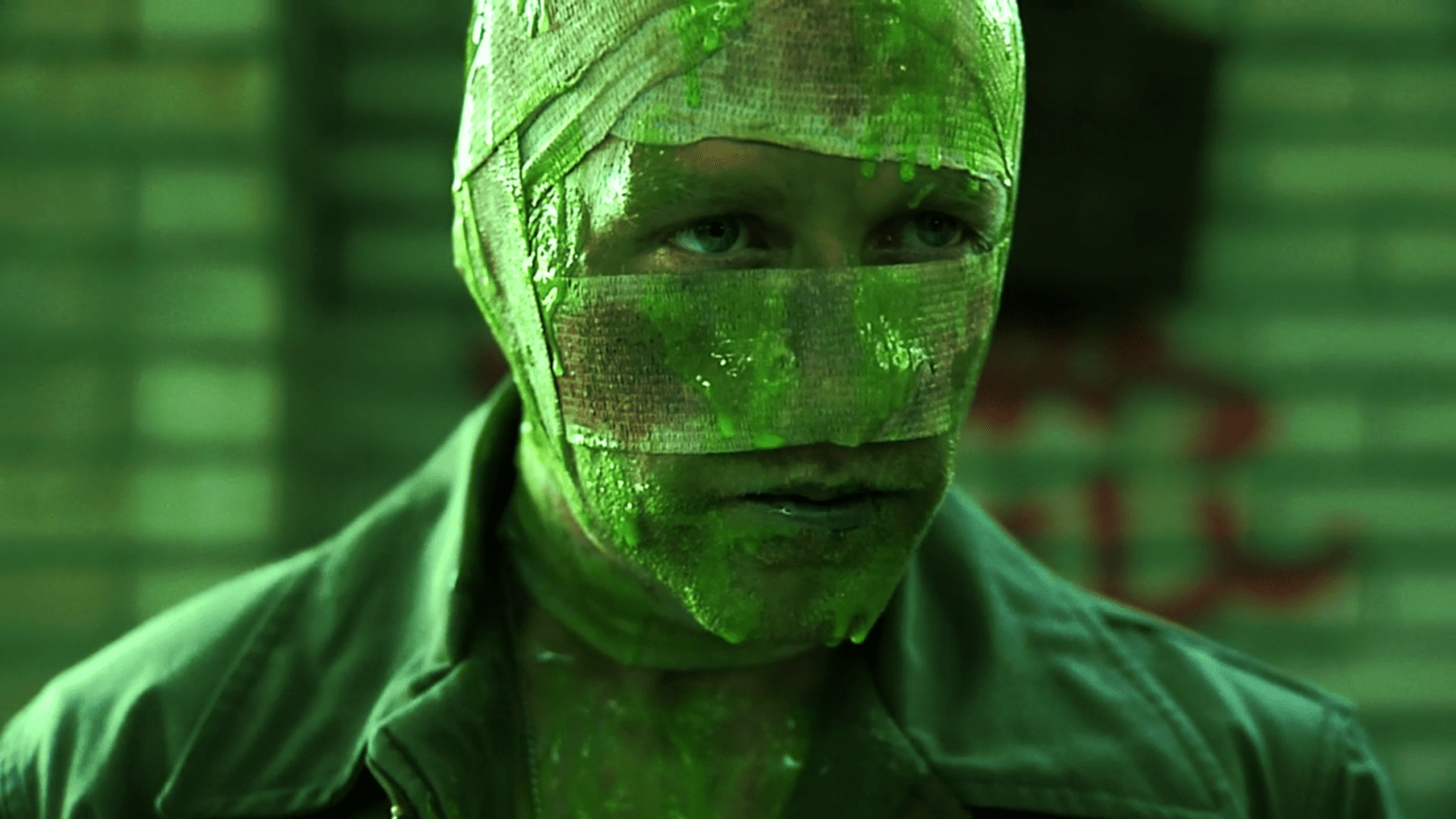

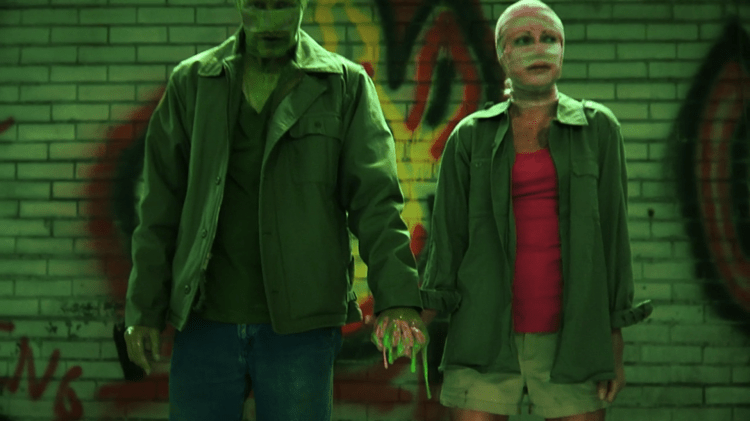

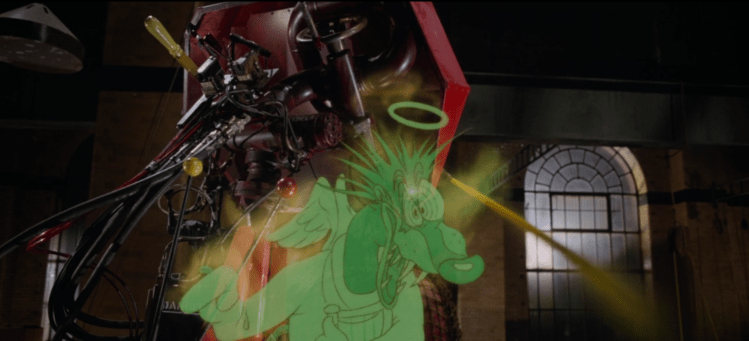

Or (*38-year-old spoiler) the scene when Doom is revealed to himself be a cartoon. He’s flattened with a steamroller, while, as the closed captioning states, “screaming” and “gibbering.” His fake eyes fall out to reveal crazed animated orbs, and he wastes no time attempting to kill everyone around him with his toon superpowers.

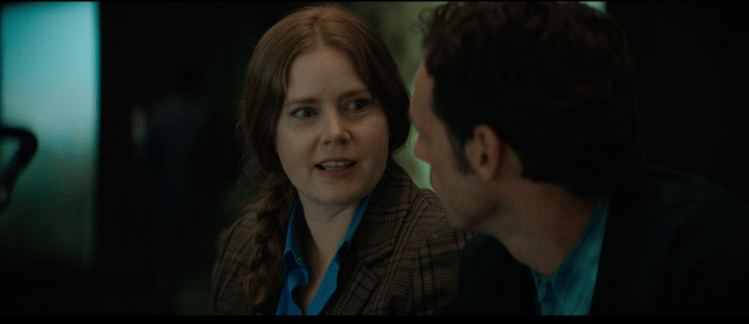

2. All Dogs Go to Heaven

Another Don Bluth classic. New Orleans, 1939. Charlie is a seedy German shepherd out to gamble and have a good time at others’ expense. When his business partner murders him so he can have all the profits for himself, he gets Charlie drunk and runs him over with a car. Charlie is able to trick his way back to earth, heedless of the warning that he can never come back, and continues business as usual, this time with virtuous orphan Anne-Marie, who can talk to animals. Since it is (ostensibly) a childrens’ movie, he learns a lesson about not being a cunt and is able to return to heaven at the end.

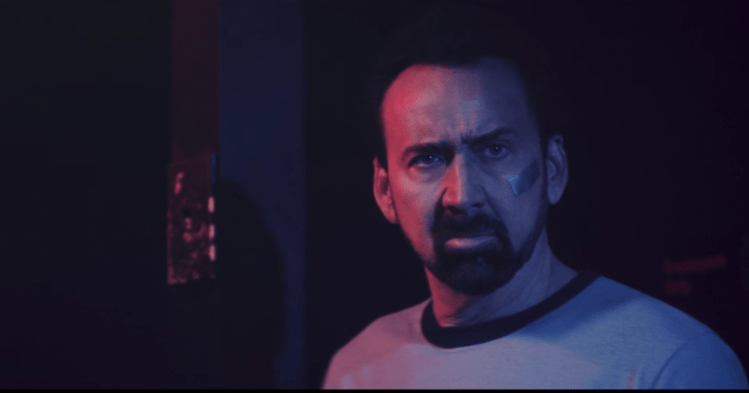

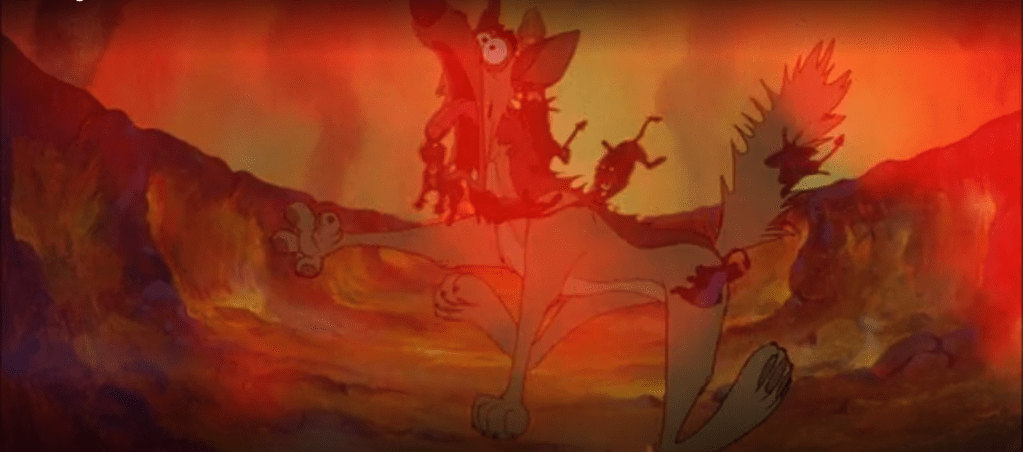

The following sequence is a dream Charlie has about being condemned to hell, complete with lava lakes, skeletal pterodactyls, and mini-demons who bite him mercilessly.

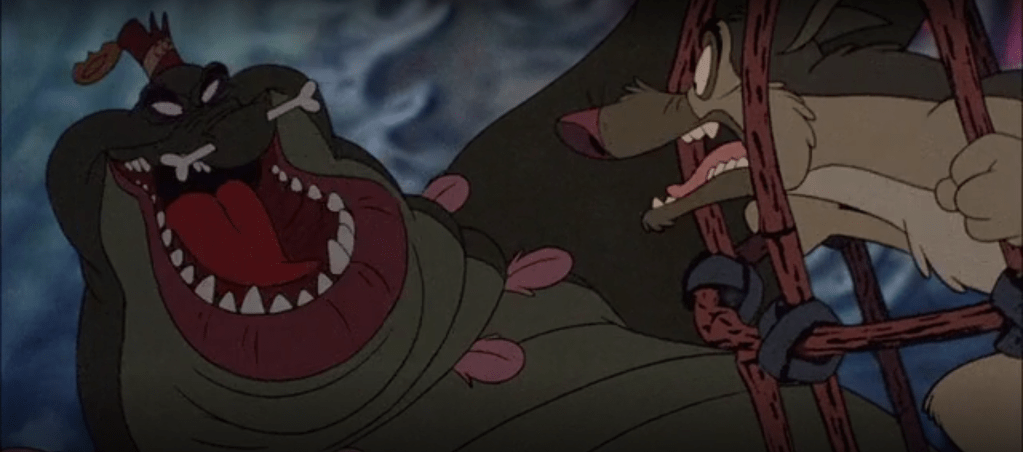

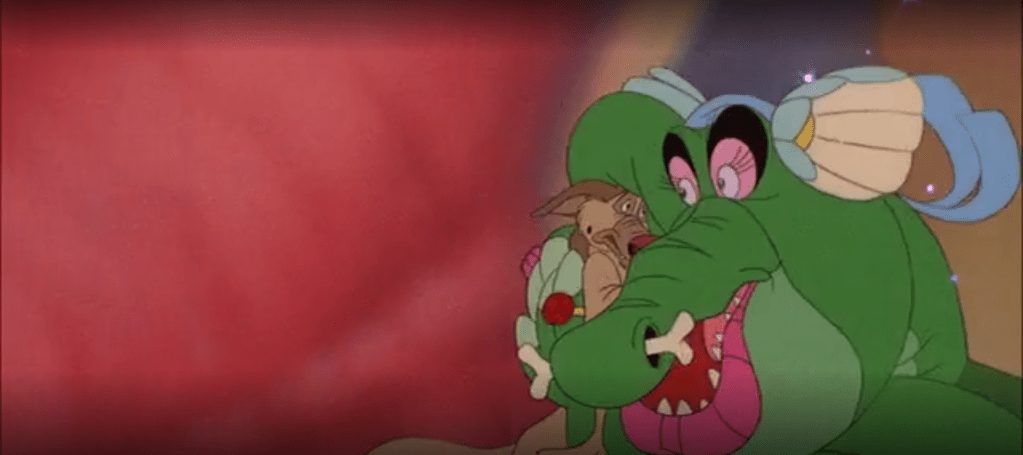

However, the far more disturbing scene is when Charlie and Anne-Marie are held hostage by a gang of rats that appear to be what white people think African people look like. Anne-Marie is unable to communicate with them because “They talk funny.” Then their boss shows up, an alligator with a bone through his nose and decidedly more generous lips than a cartoon alligator would typically have. And yes, it is a Black gentleman who voices him. Not only is it blatantly offensive, it has such little bearing on the plot that it would go on to spur its own movie trope, known as the big-lipped alligator moment. To add insult to injury, the gator goes from menacing to a fawning gay stereotype after his attempt to eat Charlie results in a howl that impresses him with its musicality. (Which is ironic because voice actor Burt Reynolds garnered a lot of complaints about Charlie’s singing.) The reptile dons a flowered headpiece and grows eyelashes and makeup out of nowhere and sings a love song to Charlie about making music together.

Is this better or worse than my number one pick? Well, at least this movie has Melba Moore:

1. The Elmchanted Forest

This is a Croatian/American effort, the internets tell me. I watched this many, many times as a young child, and for the life of me I don’t know why I liked it so much. The animation is just ugly.

The writers’ idea of humor is endless lazy puns and ethnic stereotypes such as a lizard who sounds like Super Mario and a French fox (also the only female character who has any significant dialogue) who spends her screentime being vain and coy. So to sum up the plot, Peter is a painter who is magic-ed by a tree to make him understand the forest animals. They’re being menaced by the bitter Emperor Spine, who’s set on decimating the woodlands. The animals are obnoxious, from cutesy hedgehogs who say things like “Yummy tummy!” to a sports-obsessed bear and a beaver who makes horrible clicking noises. There are multiple scenes that dissolve into blood-curdling psychadelic sequences for no particular reason:

When I was a kid, the only thing I found off-putting was a scene when the Cactus King’s servant is imprisoned in a tower to await execution by shredding machine. There’s an ominous mega-’80s song with tubular bells and a drum machine playing in the background. Don’t ask me why a giant robotic guillotine needs a shredding machine.

As an adult, the entire film is off-putting, but the worst offender is the sequence when Peter is trapped in a cave underground with mushroom creatures who want to turn him into one of them. When he refuses, they sing a creepy song and grow fangs. If you’ve never heard of this movie it’s probably because it hasn’t been released on DVD in the US in 25 years because the head of security and his three backup singers look just like historic racist caricatures of Black people:

I can’t make light of something so disgusting, especially because my white privilege allowed me to completely forget this scene existed–not that I would have recognized blackface imagery as an elementary schooler anyway. But I can’t leave you without a palate cleanser, so here’s Janelle Monáe:

And because I can, here’s a vintage clip of national treasure Maru, the delightfully chonky Scottish fold from Japan:

Sweet dreams!